Posted by Abby Barrett, GD Poetry Reader for 7.1

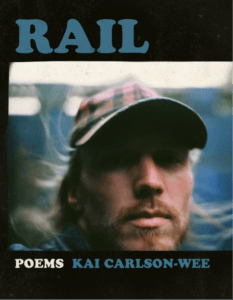

In Kai Carlson-Wee’s RAIL, desperate yet autonomous speakers view the beautiful landscapes of western America from the vantage point of moving trains, and their journeys illustrate how U.S. capitalistic values destroy this same landscape and the human dreams within. The speakers in Carlson-Wee’s poems observe pollution, watch animals die, and smoke crystal meth; they embrace a lover, listen mournfully to the loon’s cry, and self-medicate with orange juice and oatmeal. There is at once a drive for existence in these speakers; “Her breath made me shake. / It was full of so much life. For the next / few days I could hear it in every word I said” (67), and yet, a fear of what this life holds: “We are held in a light so perfect it grows inconsistent. / Becomes like the windwheel cries on the prairie” (46).

In Kai Carlson-Wee’s RAIL, desperate yet autonomous speakers view the beautiful landscapes of western America from the vantage point of moving trains, and their journeys illustrate how U.S. capitalistic values destroy this same landscape and the human dreams within. The speakers in Carlson-Wee’s poems observe pollution, watch animals die, and smoke crystal meth; they embrace a lover, listen mournfully to the loon’s cry, and self-medicate with orange juice and oatmeal. There is at once a drive for existence in these speakers; “Her breath made me shake. / It was full of so much life. For the next / few days I could hear it in every word I said” (67), and yet, a fear of what this life holds: “We are held in a light so perfect it grows inconsistent. / Becomes like the windwheel cries on the prairie” (46).

For Kai Carlson-Wee, as well as his brother Anders (also a poet, with whom he’s created several films) American capitalism is like a beast that extinguishes the joy of life and nature. Anders says it this way: “Regarding the folkloric history in the United States, trains have simultaneously represented the dream of the West, and the death of that dream by the hands of capitalism and greed.” He describes one of his and Kai’s favorite places to play as boys—“the orange tailing piles of the abandoned copper mine—a wasteland that continues to pollute the region.” Kai’s poems in RAIL are continually representing nature, both as it’s seen from the train tracks, as well as how it’s polluted by capitalist industrial bodies and machines. American capitalism illustrates “blood on the tracks” when his poems discuss death, drug use, poverty, and depression. For example, Carlson-Wee makes many references to his speakers taking prescription medication, as in “Mental Health” and “Riding the Highline,” and yet, these same speakers are often homeless and hungry. Thus, Carlson-Wee’s poems in RAIL characterize American capitalism both by its emphasis on profit (prescription medication) and inequality (homelessness), and how, in America, these exploitations are often simultaneous. American capitalism is a lens through which the poems are filtered, each of them experiencing their own inequality-based violence. Perhaps this is why Carlson-Wee’s speakers are often fearful about what life holds—they see pain before they can experience beauty.

This fear of what life holds is grounded in sensory images in Carlson-Wee’s poems. Violence acts as a response to vivacity, as in “Steampipe,” in which a tadpole is dropped into a boiling meth pipe: “The one man laughs as the first man takes / a hit, and the spinning body, writhing now, / knocking its head against the glass, / begins to glow” (45). The image Carlson-Wee creates, with two men laughing at a tiny scalding specimen and the speaker passively observing, creates an emotional response of uncertainty and sorrow. Carlson-Wee’s speaker sees violence throughout RAIL, as in “Pike”: “Her father removing a worm from / the loose earth, threading the wet pink flesh / with a hook. Dirt on his fingers. The long / bleeding body in agony, curling to feel / its way up the nylon line” (65). Carlson-Wee portrays this act of fishing, which is a commonality to so many people, as an “agony” while the worm attempts to escape its fate. However small the creature, Carlson-Wee’s speakers are attuned to their pain, and I appreciate this generosity and closeness in focus.

To further complicate the vivacity of life, and portray his speakers’ uncertainties, Carlson-Wee explores not only violence and suffering, but also death, in “Depression,” for example, which concludes: “the swallows leave the shadow for the bridge / and the carp float dead in the metal grates below” (19). More horrifying are the grotesque images of human deaths, such as in “After Havre” and “The Boy’s Head,” both in section II. In particular, Carlson-Wee has noted in an interview that “After Havre,” which uses an epigraph referencing a news article about a murder, symbolizes the death of the American dream: “Lost in the tar grease and prairie dust / laced on the wasted Dakotas; what do we do / with a regular dream?” (33).

The drive for life in Carlson-Wee’s poems, then, is ever-present alongside the sorrow, violence, and death. In “Crystal Meth,” the speaker describes his lover—“your flattered cheeks, your effortless, / practiced charms, the wet sheet hugging your flattened / breasts, floating like two wide lilies from one side / of your chest to the other” (46), and yet, the speaker is certain, “we ruin this beauty by calling it / substance, innocence, wilderness, babyface, girl” (47). We glimpse beauty in one moment through the speakers’ eyes, and then we see how that beauty is effaced and destroyed. “This is the best / I can give for a reason—the metal accepts you, / whoever you are. The train you are riding will only / go forward” (29). Ultimately in RAIL, there is a quiet, inevitable sort of acquiescing to the capitalist mode and loss of the American dream. As Anders mentioned, the trains symbolize both the American dream and the death of that dream, and these speakers are set on riding the rails. I am reminded of the age-old story of beauty and the beast, in which pain and splendor are contained together and wrapped up inside one another—as in Kai’s “O Day Full of Grace”: “To become like the song / and the silence inside it, the speed of those roads / in the wake of it leaving, that horrible beautiful sound” (95).