Posted by Evan Goldstein, GD Managing Editor for 5.2

Posted by Evan Goldstein, GD Managing Editor for 5.2

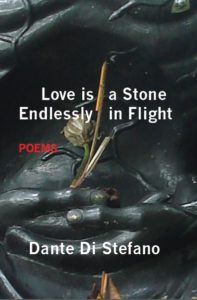

I finished Love is a Stone Endlessly in Flight, Dante Di Stefano’s debut poetry collection, alone under the harsh fluorescent lamp that hangs above my dinner table. It was a frigid winter night, and the wind howled its way under the door to my house and into the living room. Earlier, I had spent considerable time looking out of my bedroom window: trash and lost milk crates skated across the concrete past the students fighting their way to campus in the wind.

It’s easy, especially on Western New York winter nights like this, to feel unhopeful. We live in an unhopeful time, as well. As we watch the authoritarian Trump administration double down on America’s long bipartisan history of war abroad and austerity and state terror at home it can be easy to forget where to find hope, or at least solace, in the day by day.

Dante Di Stefano—a poet, essayist, reviewer, high school teacher, and State University of New York graduate—in addition to his work compiling the anthology Misrepresented People: Poetic Responses to Trump’s America, seeks to find this hope in poetry and art itself. His poems live in this same suffering world, discussing everything from his father’s death, to immigration, to rural isolation, train depot graffiti, and the decline of cities like his hometown— Binghamton, NY. Still Love is a Stone Endlessly in Flight is a journey into the source of—and reasons for—hope in our time. On the backdrop of intense suffering, Dante paints a vibrant argument for the necessity of art, of poetry, in fighting for hope and humanity.

Be it a search for God or a search for Poetry, Love is a Stone travels far and wide. From William Carlos Williams’ poetic Paterson New Jersey, to the bus in Binghamton, to a supermarket parking lot, to a Holiday Inn dumpster, to the voices of blues and jazz musicians like Junior Kimbrough and Coltrane—we follow the speakers of these poems as they search for the poetic in a world where beauty and art seem to be disappearing.

With enough attention, enough consideration, anything can be beautiful in Love is a Stone.

Dante finds the beautiful in the quotidian, transforming, in “Chagall’s Bride on the Leroy Street Bus” the “old lady / in the seat across the aisle” into a vision from Chagall’s ecstatic painting, and then resolving into ordinary beauty: someone who “could be an angel, / or my grandmother come back to life, framed / by a bus window dappled with cobalt blue rain.”

Many of the poems in Love is a Stone are personal, revolving around the author’s childhood, and his coping with his father’s recent death. The collection signals its embrace of the personal in “A Defense of Confessional Poetry,” which operates almost as a counterargument to the criticism that the confessional poetry is self-indulgent or a-political.

Here, the personal is transcendent, allowing these poems to explore the grand themes of death, sorrow, class and racial conflict, without veering into the grandiose—all while maintaining honesty and emotional intensity. Dante achieves this honesty and intensity through masterful attention to the line-as-a-unit, and through repeated images that gain meaning and momentum throughout the book. Consider, for instance, the last sentence of “A Defense of Confessional Poetry,” which pushes its syntax over 16 lines, allowing it to gain momentum and intensity as it describes his dying father’s vision of heaven:

However, this is just an unclear way

for a son, whom both you and I well know

cannot yet speak his sorrows to the stones

at orchard edge, to tell of how he felt

when his father told him that he wanted

to die and that he dreamt heaven a roof

at the post office where he worked for years,

thirty years, and on this roof his mother

danced with her arms open, calling him home

to dance in the open air, in place

without clocks or hospitals, where hearses

don’t stop, and his face has not wasted a shade

of yellow, the color of which has only

been known in the tints of Chagall’s tall grasses

and in the lost fabrics woven during

the declining years of a fallen empire.

There is a poem in Love is a Stone Endlessly in Flight for everyone. Gandy Dancer has known Dante’s poetry for years, since we published him in issue 3.2 and in the postscript of issue 4.2. In Love is a Stone Endlessly in Flight, Dante has yet again shown the craft, care, and perspective that drew us to his work from the start. Not only is this collect a well-paced work with varying styles, pleasing attention to the effects of craft, and a wide thematic scope—it is an important work, as well, because it argues on behalf of poetry, of art, as integral to life itself—as a thing we can’t live well without. It also argues that there is hope for humanity—even in the darkest of times.

In an interview Dante gave for Best American Poetry’s blog, he summed up the reason why he, and I think many of us, dedicate ourselves to reading and writing, even when we’re told it has no purpose: “Poetry at its finest affirms the dignity of human life, a dignity which fountains through even the worst degradation and the most profound suffering.” If poetry at its finest affirms human dignity, then Love is a Stone Endlessly in Flight certainly is poetry at its finest.