Posted by Caitlin O’Brien, Poetry Editor for issue 4.2

As the frenzied period of submissions review winds to a close, I find myself growing a little tired of white space. White space is almost invariably inescapable when putting together a literary magazine, and perhaps even more so when dealing with poetry, yet I’ve noticed a recurring aesthetic trend of white space in many of the submissions we read. From both a literary and an aesthetic standpoint, I can’t help but find this trend in poetry to oftentimes border on excessive. This is not coming from a staunch poetry elitist who refuses to read anything written after the 1800s—I love seeing poetry as a written art form interface with the visual, as well as with the spoken, and other modes of communication.

What gives me pause when I encounter a poem that makes ample use of white space is the intentionality behind its form. In the case of some submissions, the poets submitting to Gandy have made wonderful use of white space—we’ve received calligrams in clever shapes, as well as poems that can be read in multiple ways due to the way the words and stanzas are arranged. In the case of other submissions, though, the poetry team has often used the deliberative construction of the poem’s form as a strong measure of the poem’s overall purpose. Reading a poem aloud, the white space does not always inform the flow, so much as it makes the poem seem as though the poet was possessed of a hyperactive space bar. The most common aural effect of a form that relies on white space is a pause, yet these pauses do not create a rhythm that comes across as calculated. As one reader in the poetry section said, “if we have to guess whether or not the poet meant to do something, it’s not effective.” Similarly, the primary visual effect of non-traditional spacing is to set apart important words or allow the reader to focus in on a particular image or concept, rather than jamming the space bar an arbitrary number of times in order to make a poem look modern and minimalist.

Continue reading →

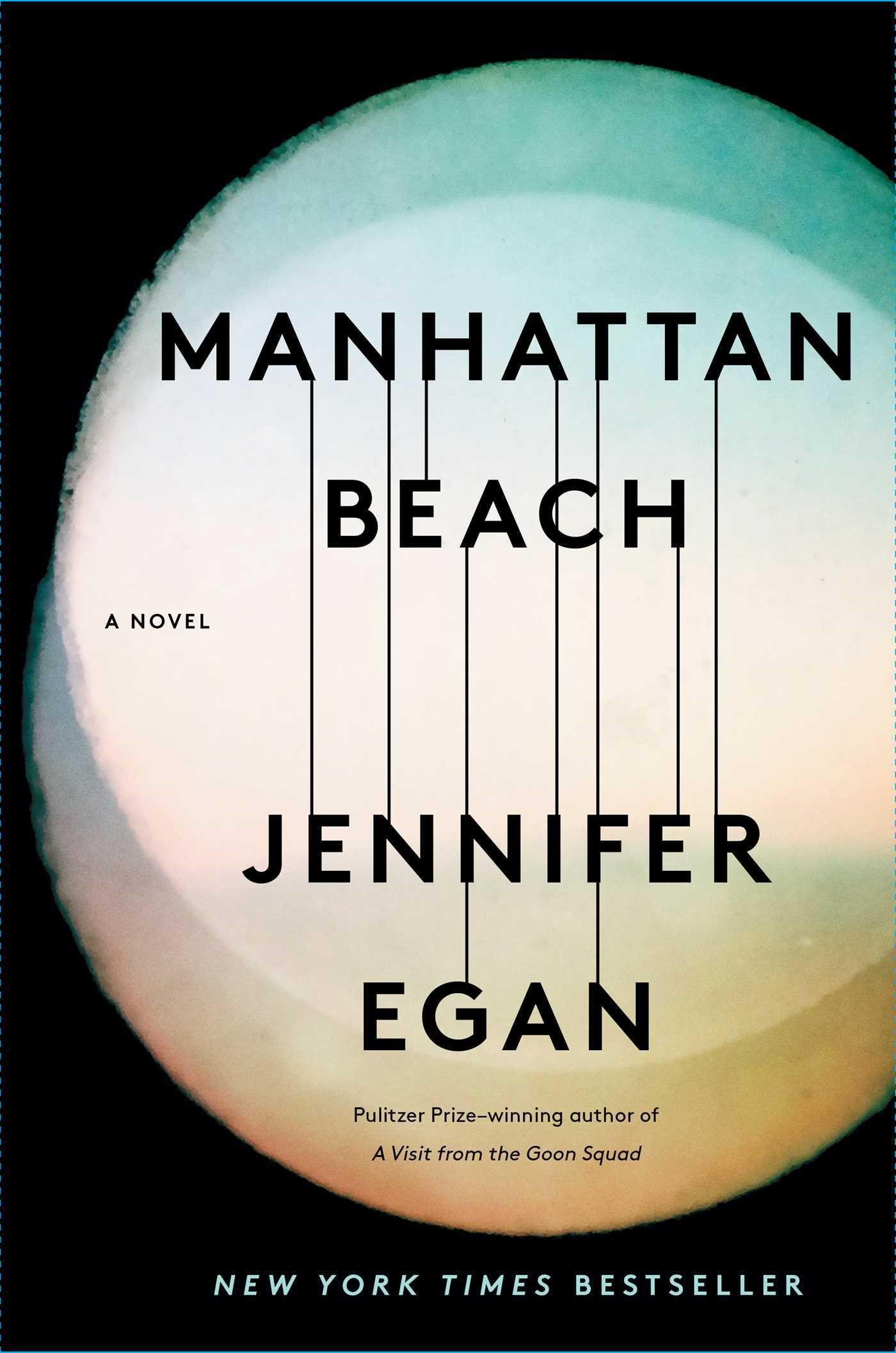

I invite you to refute the old adage “don’t judge a book by its cover,” and contemplate the paperback edition of Jennifer Egan’s A Visit from the Goon Squad, published in 2011 by Alfred A Knopf. The cover shows a colorful menagerie of bodies in manifold contortions and postures. The translucent figures overlap and blend with each other, but no single figure grabs a central focus. The book’s title is laid over this image (again, the font is translucent) and the cluster of bodies is put into focus by a background of stark white space. The cover suggests not cacophony but polyphony, its narratives not shouting over one another but offering a variety of perspectives and lenses through which readers can continuously re-interpret the cover. Continue reading

I invite you to refute the old adage “don’t judge a book by its cover,” and contemplate the paperback edition of Jennifer Egan’s A Visit from the Goon Squad, published in 2011 by Alfred A Knopf. The cover shows a colorful menagerie of bodies in manifold contortions and postures. The translucent figures overlap and blend with each other, but no single figure grabs a central focus. The book’s title is laid over this image (again, the font is translucent) and the cluster of bodies is put into focus by a background of stark white space. The cover suggests not cacophony but polyphony, its narratives not shouting over one another but offering a variety of perspectives and lenses through which readers can continuously re-interpret the cover. Continue reading